Blog

Israel's Immigration Laws

Wednesday, March 20, 2019

For several years, one of the hot-button issues in American politics has been the subject of immigration. Such things aren’t really the concern of me or my blog. However, through the years, I’ve seen a lot of Scriptures quoted out of context in memes from both sides, and that is my concern. I don’t have any answers for what the United States should do in 2019, but I think it’s worthwhile to consider what God says on the subject and use it as a starting point for our own views.

First of all, immigration simply isn’t a New-Testament topic. The law of Christ is concerned with the Christian’s relationship with the government, but it has nothing to say about how governments should conduct themselves. Christ’s kingdom is not of this world.

However, the same is not true of the Old Testament. The law of Moses is no longer in force, but unlike the law of Christ, it does have to do with the proper conduct of a government. This legal code does not bind us today, but it does give us some insight into how God might look at a particular legal topic. Indeed, there are many passages in the Pentateuch that discuss the treatment of what the ESV calls “sojourners”:

- The law had no rules restricting the movement of sojourners into Israel. Of course, this may be because a Bronze Age confederation/kingdom had no means of enforcing border security, but it’s worth noting. Sojourners did not automatically become Israelites by entering the land, but they were free to enter.

- Sojourners were to be treated lovingly (Deuteronomy 10:19) and justly (Deuteronomy 20:17).

- They had the same rights and the same obligations under the law as native Israelites (Leviticus 24:22; Numbers 15:15-16).

- They were expected to follow many of the religious requirements of the Law (Exodus 12:19, 20:10; Leviticus 17:15; Deuteronomy 5:14). They were also free to participate in some other rituals if they chose (e.g. Leviticus 22:18).

- They were to be provided for by the natives, but only to the extent that they were willing to work. A wheatfield owner had to leave the corners of his field unreaped and the whole ungleaned (Leviticus 23:22), nor could he return to retrieve a sheaf he had forgotten (Deuteronomy 24:19). Olive grove and vineyard owners couldn’t go back over the trees/vines after they had done so once (Deuteronomy 24:20-21).

- In all cases, this was for the benefit of the widow, the fatherless, and the sojourner. None of the poor could expect their meals to be delivered to their doors if they sat at home, but they could get food for themselves if they were willing to go out and harvest it.

- These provisions existed because God loved the sojourner, just as God loved the widow, the fatherless, and all other weak, vulnerable people (Deuteronomy 10:18).

Again, none of these things determine for us how the United States should handle those who want to immigrate to it. However, if we want to use the word of God to develop and defend our positions (whatever they might be), appreciating the whole counsel of God can only help.

Who Is God?

Tuesday, March 19, 2019

Even foolish people can ask good questions, and one of the best Biblical examples of this appears in Exodus 5:2. I think that Pharaoh meant this question sarcastically, even though God spends the next 10 chapters of Exodus cluing him in. For us, though, it’s a question that we should ask non-sarcastically because the answer is important to all of us.

After all, we know that there is some kind of super-powerful being that we might as well call “God”. We see His handiwork revealed both in the physical creation and in the Bible. However, lots of people have all kinds of wrong ideas about this God because they don’t pay attention to what He has revealed about Himself. Instead, they make up their own version.

If we want to teach others, we have to know how to combat this kind of ignorance. This sermon, then, is going to be the second sermon in our study-outline series. It will help us to lead an outsider through a half-hour study that will answer the question, “Who is God?”

The first thing that we must understand about Him is that HE IS THE CREATOR. Look here at Revelation 4:10-11. In this text, there are two points that I want to focus on. The first is that if it exists, God made it. We are not here as the result of some mindless Big Bang. All of the creatures on earth are not here because some protoplasm evolved in a volcanic vent on the sea floor. Instead, we are here because God spoke and created us.

Some people find this hard to believe. You know what I find hard to believe? I find it hard to believe that the universe came about by chance. It would be like if Marky dumped out a bin of Legos on the floor and they all just happened to fall together to create a perfect model of the Millennium Falcon. Brethren, if I come into our family room, and I find a perfect model of the Millennium Falcon made out of Legos, I’m going to assume that somebody built that thing! Same with all this. Somebody made it. God did.

Second, the text tells us that because God is the Creator, He is worthy to receive glory and honor and power. As long as my parents were alive, I honored them because they were my parents. They brought me into this world, and the whole time I was under their roof, they provided for me. The same is true for God. Because He made us and provides for us, He is worthy of our worship.

It is also true of God that HE IS GOOD. Consider the exchange recorded in Mark 10:17-18. I think that when Jesus says that no one is good except God, He is including Himself in that as deity, but it’s still a true statement. Only God is good.

I think this is true first in the sense that no one is as good as God. He is the highest expression of every virtue, and He is constant in being virtuous. None of the rest of us can make that claim. I try to be a loving person, but I know very well that my love for others pales in comparison to the perfect love of God. I know too that there are times when I am not loving at all, when I am apathetic or downright hateful. God is not like that. His love is as constant as the sunshine on a cloudless day. God always loves, no matter what.

Second, God is the standard for goodness. Because He is perfect, we can’t look to ourselves to determine what is right and wrong. We have to look to Him. Lots of people in our society get this backwards. They think that they have the right to determine what is good and what is evil. In fact, many of them criticize the word of God because they don’t agree with it.

Brethren, that’s about like me criticizing a yardstick because I don’t like what it says about how long three feet is! I’m not the standard for three feet. A yardstick is. Neither are we the standard for good and evil. God is.

Third, GOD IS HOLY. We see this in the praise of the seraphim in Isaiah 6:1-3. Holiness is a tough thing to define, but I think that ultimately it consists of the idea of being separate. This is true of God in two main ways.

First, He is holy in His high position. This is hard for Americans to realize. We’re raised from infancy to believe that we’re just as good as anybody else. Well, when it comes to God, we aren’t. It would be weird if any of us had somebody following us around literally singing our praises all the time, but that’s not weird for God. It’s appropriate. That’s what He deserves.

Second, God is holy in His separation from sin. We’ve already seen that God is perfectly good, and because He is perfectly good, He is incapable of tolerating evil. People who think that they can do whatever they want and God doesn’t care could not be more mistaken.

Imagine the most disgusting thing you can think of, and the way your whole being revolts at it. That’s how God is with sin. He can’t stand to be around it. If we come before Him in our sins, we will leave Him no choice but to cast us out of His presence forever.

Finally, despite our evil, it is still true that HE DESIRES A RELATIONSHIP WITH US. We see one of the most beautiful expressions of this desire in 2 Corinthians 6:17-18. Let’s pause for a moment to reflect on how amazing this. We know that God is more important than we are. We know that God is better than we are. Nonetheless, the perfection of God’s love is so great that He continues to love each one of us. What He wants is to be a Father to each one of us, to have each one of us as His sons and as His daughters, not only now but forever. No matter what anybody else says or does, all of us matter to God.

However, this relationship can’t be on our terms. It has to be on God’s terms. If we want to be His children, we can’t be like all the people who don’t care about Him. We can’t walk in the footsteps of the wicked world. Instead, we have to come out of the world. We have to seek separation and holiness so that we can be like Him.

Once we have done that, we can’t love unclean things anymore. We can’t continue in sin, even in our favorite sin. We have to love God more than we love it. If we truly love God, we will not demand that He compromise His holiness for us. Instead, we will get all of the compromises out of our lives so that we will become like Him. If we refuse, if we cling to our sin and expect God to like it, we have forgotten who is the Creator and who is the creation.

Chapter Summaries, Job 11-15

Monday, March 18, 2019

Job 11 marks the first time that Zophar the Naamathite speaks up. He is the most sarcastic of Job’s friends so far. He begins by expressing his contempt for Job’s “babble” and his hope that God would show up to set Job straight. He then caustically questions the limits of Job’s understanding of God. Who does Job think he is, that he can call God to account? Finally, Zophar returns to a familiar theme. All of Job’s problems are the result of his sin. If he acknowledges his sin, his problems will disappear and his life will be good again.

Job 12 is the beginning of Job’s equally sarcastic reply to Zophar. He resents Zophar’s mockery of him, particularly when Zophar thinks that he himself is sooo wise. However, Zophar has overlooked the fact that the wicked are prospering while righteous Job is suffering.

Next, Job points out that his suffering must be the result of God’s action. All created things reveal the power of the Creator. In fact, God is omnipotent. Nobody can control or restrain Him. Even the most prominent and powerful people cannot stand against His will.

Job 13 continues Job’s dissection of Zophar’s claims. Job wants a hearing before God, but in insisting that Job has no right to such a hearing, his friends are misrepresenting God. They’re being unfair to Job, and God will punish them for it.

After this, Job directly addresses God again. He says that he will continue to hope in God even if God kills him. He knows that he is righteous, so he has the right to come before God. From God, Job wants to learn two things. First, what has Job done wrong? Second, why does God hate him and persecute him so much?

Job 14 is the conclusion of Job’s rebuttal. He begins by describing the transitory nature of man, who is not eternal because God has chosen that he should not be eternal. A tree that is cut down may sprout from the stump, but man, once dead, stays dead. What Job would really like, if God is this angry at him, is for God to kill him now and resurrect him once God’s wrath is past. However, Job knows that this is a vain hope. Instead, he is going to have to continue in his suffering.

Job 15 contains the next speech of Eliphaz. He says that Job is being a windbag, hindering faith in God, and revealing his own sin with every word. Like Zophar, he demands to know who Job thinks he is, that he has the right to question the justice of God and the understanding of his friends, who apparently are much older than he is. Why is Job so angry when all people are inevitably wicked? Eliphaz then spends the remainder of the chapter elaborating on the fate of the wicked. They oppose themselves to God, so they can only receive evil and not good.

Psalm 23

Friday, March 15, 2019

My shepherd is the Lord;

He gives me all I need.

He makes me lie in pleasant fields

Where I may rest and feed.

Beside untroubled streams,

The Lord renews my soul.

For His name’s sake, He leads my feet

On paths that reach the goal.

I will not fear the way

When You are there, O God;

My comfort through the darkest vale

Will be Your staff and rod.

Before my foes, You set

A place for me to sup;

You pour out oil upon my head,

And blessing fills my cup.

The Lord will follow me

With grace and faithful love,

And I will dwell within His house

Through endless days above.

Understanding God's Will

Thursday, March 14, 2019

Last week, I mentioned that Sister Margaret and I had had some conversations about me providing some basic outlines that the members here could use to study with others. I thought that was a wonderful idea, so I solicited outline topics from y’all.

I got several suggestions, and I had a few ideas of my own. This morning, I’m going to be presenting the first of those outlines. My hope for this sermon, and for all others in this series, is that it will equip you to lead a short, half-hour study with somebody on this topic.

Logically speaking, the study I’m about to present has to come at the very beginning. I can teach somebody any number of things from the Bible, but before that, we have to agree on what the Bible is and the significance of what it says. Without that, what makes the Bible any different than some self-help book I pull off the shelf at Barnes & Noble? For that matter, what makes the words of the Bible different than the words of some random priest or pastor? These are important questions, and we need to answer them by understanding what the Scripture says about understanding God’s will.

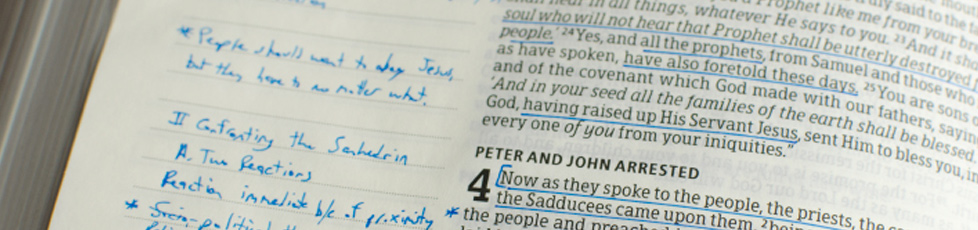

The first issue that we must settle from the word is HOW GOD SPEAKS TO US. Consider here Paul’s words in Ephesians 3:4-5. Notice that this passage describes a process. This begins with the mystery of Christ. Here, I don’t think that Paul means that Christ Himself is mysterious. Instead, I think the point is that Christ had a mystery, some unrevealed thing. The Holy Spirit took that mystery of Christ and revealed it to God’s apostles and prophets, of which Paul was one. Paul wrote that revelation down in the book of Ephesians. The church in Ephesus then could read what Paul had written and perceive his insight into the mystery of Christ. This is how God reveals His will to His people.

This is extremely important for a number of different reasons. First, there are plenty of people out there who think that God speaks to them directly. A question to ask them from this text is “Do you think you’re an apostle or a prophet?” If they do, well, a little later, we’re going to be doing a study on spiritual gifts, and that would be a good thing to study with them! If they don’t, then they are not the recipients of revelation. Only apostles and prophets are inspired.

Second, we need to pay particular attention to what Paul says in Ephesians 3:4. Speaking to the ordinary Christians of the Ephesian church, he tells them that they could read his letter and understand his insight into Christ’s mystery. By extension, when we read the Scriptures today, we can understand Christ’s mystery too.

It’s almost impossible to overstate how important and empowering this is. There are whole denominations out there that are founded on the notion that ordinary Christians can’t understand the will of God for themselves. Well, the apostle Paul tells us that we can understand it!

This is not to say that figuring out God’s will from His word will always be easy for us. Nor is it to say that we can’t make mistakes, or that we won’t grow in our understanding. Figuring out God’s will takes work and skill.

However, it is possible. It’s possible for me, it’s possible for you, and it’s possible for everyone who is spiritually accountable. God has given us the power to learn the truth for ourselves, and that is a beautiful thing!

Next, we have to see what the Bible says about THE RELIABILITY OF SCRIPTURE. Consider the words of Peter, another one of those inspired apostles, in 2 Peter 1:19-21. Once again, there are many things to note in this passage. First, though we might think of prophecy as only foretelling the future, in this passage, the word has a broader meaning. It’s not only about foretelling. It’s about forthtelling. It’s about revealing the will of God.

Second, Peter says that these foretellings and forthtellings are fully confirmed. Particularly important here is the Bible’s record of fulfilled prophecy. If the Bible isn’t the word of God, how come David could predict in Psalm 22, a thousand years beforehand, that Jesus’ enemies would pierce His hands and His feet and gamble for His clothes? There are many other such fulfilled prophecies. They reveal that the Bible is the product of supernatural wisdom.

Third, Peter tells us that none of the prophecies of Scripture originate from human will. Instead, every one of them comes from God and the Holy Spirit. Everything in this book is inspired! The same God who can foretell the future can protect His revelation from people who want to tamper with it.

We can have confidence, then, that the books of the Old and New Testaments that we have are the books that God wants us to have. None of them are the work of human authors and ended up here by mistake. If God permits mistakes in such things, 2 Peter 1:20-21 is not true.

Additionally, God has safeguarded the contents of His revelation. Biblical skeptics like to raise a fuss over the fact that we have manuscripts of the Bible containing 100,000 variations. However, 99.99 percent of those variations are utterly insignificant, and even the more significant textual disputes do nothing to change our understanding of God’s will one way or another. In short, we can be completely certain that we can rely on the Bible as the inspired word of God.

Finally, let’s learn about THE SUFFICIENCY OF SCRIPTURE. Here, look at 2 Timothy 3:16-17. There’s a lot of meat to pull off this bone too. First, this is another passage that confirms the inspiration of the Scripture. It claims that all of it comes from God, and as we have seen before, we have good reason to believe that claim.

Second, this text describes the operation of the Scriptures in our lives. I read this as having a main heading—teaching—and three subheadings or kinds of teaching—reproof, correction, and training in righteousness. Basically, what Paul is describing here is a spiritual U-Turn. Reproof is a fancy word, but all it means is telling somebody that they’re doing wrong. In other words, “Stop going this way.” Correction is turning somebody around, “Not that way, but this way.” Then, training in righteousness is helping somebody to keep doing the right thing. “Keep going this way.”

Last, we come to Paul’s inspired views about what the Scripture can accomplish. He tells us that through them, the man of God—or woman of God, for that matter—can become complete and equipped for every good work. This is an extremely strong claim, brethren. Paul does not say mostly complete or equipped for some good works. He says complete, period, and equipped for every good work.

In other words, if we need something to make us spiritually complete, it’s in the Bible. If there’s a good work that we’re supposed to do, the Bible equips us to do it. As a result, we can conclude that the Scriptures are sufficient. We don’t need anything other than the Bible in order to please God. Everything else that anybody might say is at best unnecessary and at worst harmful.