Blog

“Reflecting on "Hoods in My Hymnal"”

Categories: Hymn Theory, M. W. Bassford

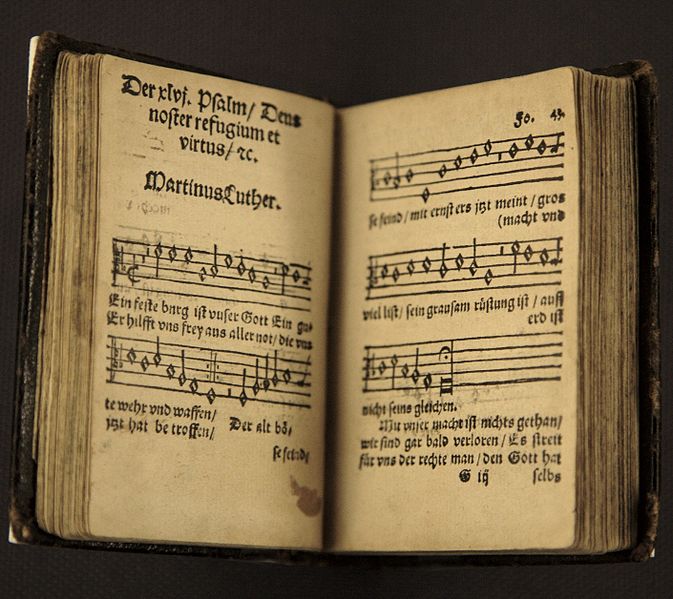

The other day, Steve Wolfgang sent me a link to this article. In it, the author points out that James D. Vaughan, founding father of the Southern gospel genre of hymnody (though not the author of “Love Lifted Me”, despite what the article implies) was a leading figure in the local Ku Klux Klan. James Rowe (who was the author of “Love Lifted Me”) wrote racist lyrics for temperance-movement songs.

This is not terribly surprising. We are talking about Southern gospel, after all, a worship-music movement which flourished in the states of the former Confederacy a hundred years ago. By modern standards, both the ones who wrote those hymns and the ones who originally sang them were dyed-in-the-wool racists. The author implies that we need to “have a conversation” about whether those hymns should remain in the repertoire, the kind of conversation that usually ends with things getting canceled.

Really, though, the issue that the article raises is much larger even than racism. How do we handle hymns that were written by people with significant spiritual problems? From the perspective of New-Testament Christianity, the most famous hymnists of all time come with baggage that is as bad or even worse.

Isaac Watts, author of “When I Survey the Wondrous Cross” and many other great hymns besides, was a hyper-Calvinist minister. Charles Wesley, who wrote “Love Divine”, was the brother and partner of John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist Church. Among modern writers, Keith and Kristyn Getty, the authors of “In Christ Alone”, are staunch and vocal Calvinists. I could say much the same about the authors of literally hundreds of the hymns in our repertoire.

Scripturally speaking, is the false teacher to be preferred to the racist?

One response is to say, “We should not sing such things.” Unless we approve of your life, we aren’t going to sing your hymn. However, if we follow through on such a conviction, our repertoire shrinks by at least 95 percent. Everything from “Abide with Me” to “As the Deer”—gone. Off to the bonfire it all goes!

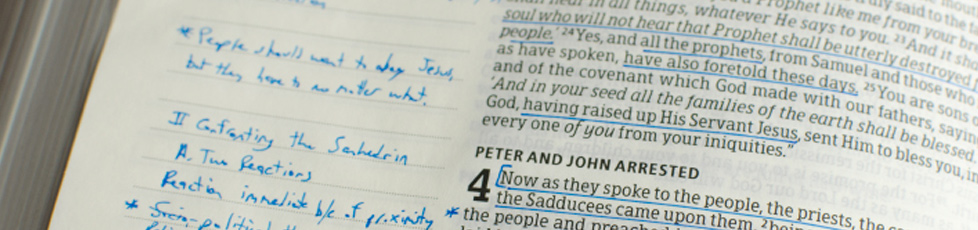

I think most brethren would consider such a solution a trifle. . . extreme. The alternative, which is what all of us do in practice, is to separate the hymn from the hymnist. I don’t have to agree with everything Isaac Watts stood for to sing “When I Survey.” I only have to agree with “When I Survey”. Nor, indeed, am I endorsing anything about Isaac Watts other than the words that I am singing.

So too, I think, with Southern-gospel hymns written by authors with murky pasts. Yes, they believed, and in some cases wrote, some awful things. However, if our minds are on the human author when we sing a hymn, our minds are in the wrong place.

Those hymns are not memorials to Confederate generals or leaders of the KKK. They are memorials to God. If we use them for their intended purpose, we are glorifying Him. To that, what Scriptural objection can be raised?