Blog

Hymn Theory

Worshiping like the Psalms

Tuesday, July 19, 2022

The other day on Facebook, I saw an article by a professor of Old Testament studies in which he compared the content of the book of Psalms to the content of Top 25 Christian contemporary music. He observed that many of the most prominent themes of the Psalms, like God's help for the poor, justice, enemies, and questioning God, are barely present in contemporary music.

I agree with that.

However, lots of people found lots of reasons to disagree with the article. Prominently, many pointed out that exactly the same charges could be made against our repertoire of traditional hymns.

I agree with that too, and I think it points out a serious problem with our song worship. Our hymns don’t engage with reality the way the Psalms do.

These days, I tend to understand the Psalms through the lens of Psalm 1. In it, the psalmist makes a bold claim about reality. He predicts that God will bless the righteous while punishing the wicked.

The rest of the Psalms put this claim to the test. Does our experience of life under the sun show God's favor toward the obedient and His condemnation of the sinner? Sometimes, the claim checks out. There are many psalms that praise God for His goodness toward His people.

Frequently, though, the Psalms address the times when God's goodness is not apparent. What about when the Israelites lose a battle despite their faithfulness? What about when the righteous are poor and oppressed by powerful enemies? What about when the sacred musicians who served in the temple are carried off into captivity alongside the disobedient? What about when the godly have failed God? There are nearly as many such questions as there are psalms.

Our hymn repertoire does a great job covering the content of Psalm 1. We often sing about how wonderful it is that God has solved our problems. However, it does a horrible job of covering the content of much of the rest of the book. We know that the life of the Christian is not always blue skies and rainbows and sunbeams from heaven, but you generally couldn't tell it from our song worship!

Consequently, our singing reinforces that pretense of perfection during our assemblies that so many brethren complain about. We know that we're going to have to paste on a smile and pretend like everything is fine when we are supposedly pouring out our hearts to God, so we might as well paste on the smile before and after services too.

Our American inability to address suffering and sorrow is part of the problem. We get super-uncomfortable when a brother tells us that actually his life is terrible. We don't know how to handle that. In the same way, many Christians get uncomfortable with singing about trial and suffering. Aren't we supposed to be putting aside the worries and cares of the world?

I think the result is tragic. Too often, hurting Christians come to worship and find that putting on a happy facade for their brethren and God is another source of stress. It feels dishonest, and it keeps them from finding comfort and authenticity in the one place where they should be able to be authentic and comforted.

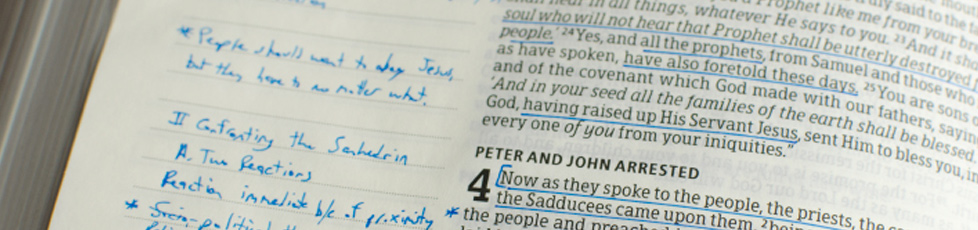

We begin to solve the problem by singing psalms of every kind, not just the upbeat ones. Since we started singing through the Psalms at Jackson Heights, I've had multiple Christians thank me tearfully for giving them the chance to finally express their feelings in worship. Sometimes, they have been so deeply moved that they couldn't even get the words out.

Second, I think all of us need to get comfortable with singing hymns about unpleasant topics, whether we ourselves are suffering or not. We require rejoicing with those who rejoice, but what about weeping with those who weep? Maybe I don't want to sing about how hard life is, but it's nearly certain that somebody in the congregation does.

I recognize that this calls for a sea change in the way that we worship. We do little lamenting, and we do no questioning or imprecating. However, it's a change well worth making. Worship like this is true at last to our lived experience.

Also, I think it is more attractive to outsiders than worship that is inright-outright-upright-downright happy all the time. Strangers don't visit a congregation because everything is going great in their lives. Instead, they come because their lives are in tatters. When they see and hear us bringing the hard things before God, they will recognize that they are in the midst of people like them.

In Praise of Hymns with Verses

Wednesday, March 03, 2021

For the past 40 years or so, the landscape of American sacred music has been dominated by the so-called “worship wars”. These (thankfully bloodless) conflicts have arisen between proponents of rhymed, metered traditional hymns and supporters of freer-form contemporary praise songs. No doctrinal issues are directly at stake here; instead, this is a question of expedience. Which form is most useful for edifying the congregation?

The a-cappella practice of the churches of Christ adds another dimension to the discussion. Most denominational churches have a performer-audience model of worship, and this model doesn’t change whether the performer is using an organ or a guitar.

Within the Lord’s church, though, we use a leader-participant model. We rely on the singing of ordinary Christians, and this reliance means that the opportunities and challenges before us differ from those before denominational worship ministers. The solutions that work for them won’t necessarily work for us, and aspects of worship music that don’t matter to them may well be vital for us.

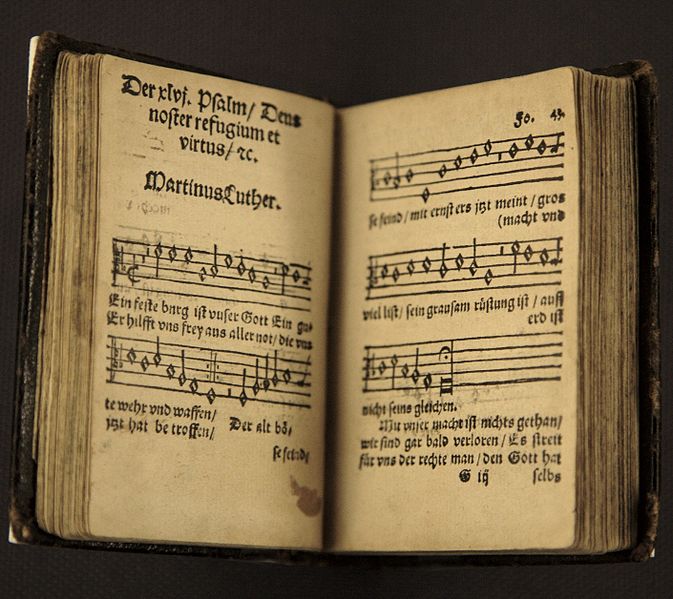

In turn, this means that we should hesitate to abandon the form of the traditional hymn. The rhymed, metered verse was not invented by Isaac Watts; rather, it is an adaptation of rhymed, metered folk song. All across Western folk music, from sea chanteys to French ballads to medieval Christmas carols, ordinary people have been singing in rhyme and meter for centuries, not because anybody made them, but because it is the form that has evolved to best facilitate the singing of ordinary people. If we also are trying to get ordinary people to sing, we ought to pay attention.

Upon examination, several traits of rhymed, metered, versed hymns commend themselves to our attention. First, they are economical in their use of music. Consider the hymn “O Thou Fount of Every Blessing”. Everyone (including us) sings it to the hymn tune NETTLETON.

NETTLETON is written in rounded-bar form, which many hymn tunes use. A rounded-bar tune consists of four phrases of music with an AABA pattern. Thus, the first, second, and fourth phrases are identical. It’s musically repetitive.

Further repetition arises through the use of multiple verses, as different lyrics are sung to the same music. Thus, by the time a congregation has sung three verses of “O Thou Fount”, it has sung the B phrase three times and the A phrase a whopping nine times.

Musicians often don’t like rounded-bar tunes. They’re bored by them. You sing the same thing over and over and over again. Yawn.

However, what seems like a stumbling block to the musician is a blessing to the congregation. Every church contains a contingent of people who complain about singing “too many new hymns” and an even larger contingent of those who feel the same way but choose to suffer in silence.

Really, though, such brethren don’t object to the new song. They object to the new tune, and they are objecting because they are not particularly musically skilled, can’t read music, and only sing in public when God commands them to. The first time a hymn is sung, they are at a loss, and they can only learn the tune slowly and painfully, by rote. Most people in most congregations fall into this category.

For decades, I’ve heard grumblings from skilled singers that these Christians need to get with the program and learn to read music. I think that solution runs in the wrong direction. Rather, we need to take account of our brethren and introduce new songs that meet them where they are. Because traditional hymns incorporate such a large amount of musical repetition, they do this well. They offer non-musicians the opportunity to sing a great deal of new content while not demanding much from them musically.

The flip side of the coin here is that while versed hymns are repetitive musically, they have the potential to be lyrically rich. The typical praise song is lyrically repetitive. Some hymns are too (and repetition to a certain extent is spiritually useful), but others work their way logically through a subject, like an essay in verse.

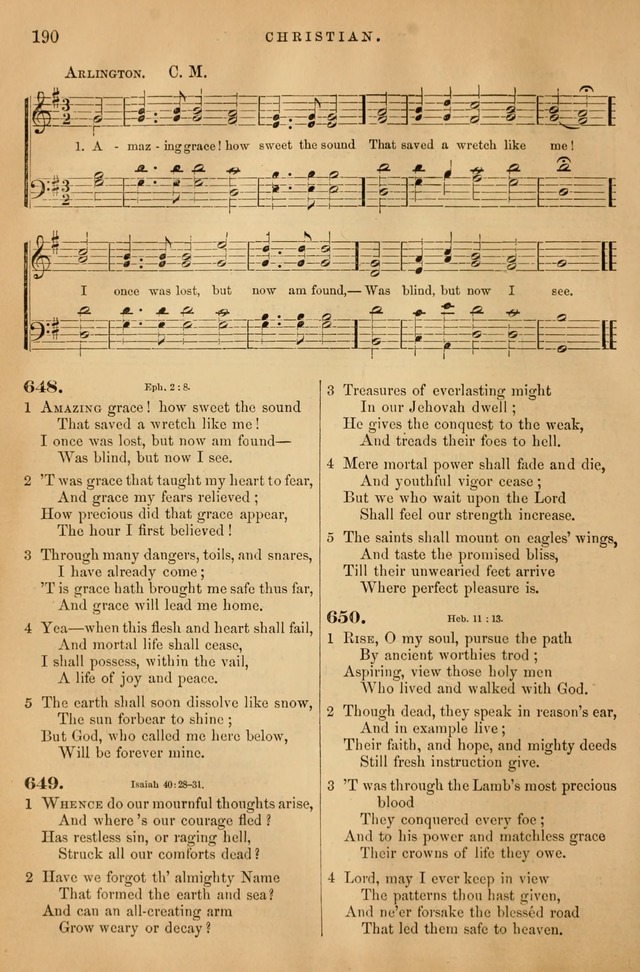

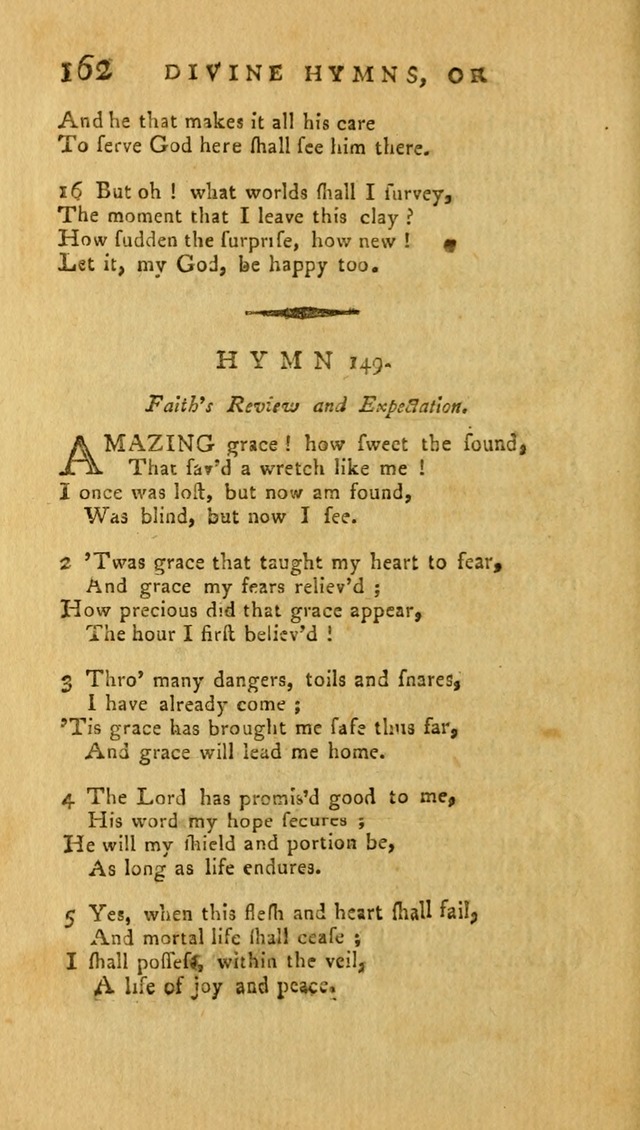

Take, for instance, “Amazing Grace”. The logical structure of the hymn is so strong that we could outline the five verses that usually appear in our hymnals as follows:

- God’s grace is amazing!

- I thought it was amazing when I first believed.

- It has brought me this far in life, and it will continue to protect me.

- It will keep me safe till the end of my life.

- I will celebrate God’s grace forever in heaven.

Hymns with such thoughtful, structured content are important for two reasons. First, they teach a great deal, which amply fulfills the divine commandment to teach and admonish in song. Second, they accustom us to following complex arguments.

It’s fashionable these days to complain about proof-texting by brethren during Bible study. Certainly, proof-texting has its uses (otherwise inspired authors would not have proof-texted), but the Bible is more than a series of proof texts. When we learn to comprehend entire arguments in the Scripture rather than focusing on isolated verses, we grow greatly in our understanding.

When we sing and pay attention to the words of a structured, content-rich hymn, we necessarily also improve our capacity for understanding the word of God. Conversely, when we sing only repetitive praise hymns that contain no more than a single verse’s worth of content, our ability to appreciate the Bible remains stunted. Our thoughtfulness in worship and our thoughtfulness in study cannot be separated.

The worship wars are not going to be settled anytime soon, and a complete victory for either side isn’t even desirable. There’s a place for contemporary praise songs in our worship services. So too, though, there ought to be a place for traditional hymns. Indeed, the more we return to these ancient forms, the more we will benefit from the wisdom behind them.

This article originally appeared in the February issue of Pressing On.

"In Christ Alone" and Penal Substitution

Friday, November 06, 2020

If there is anything in the worship traditions of the churches of Christ that frustrates me, it is the double standard of scrutiny applied to hymns with content versus hymns with no content. We have reversed the intent of Colossians 3:16, so that rather than seeking hymns that express a rich indwelling of the word, we primarily are concerned that hymns don’t teach false doctrine. As long as a hymn doesn’t teach false doctrine, it must be suitable for the congregation!

This goal produces a perverse result. Hymns that don’t teach anything obviously can’t teach false doctrine, so they slide into the repertoire without objection. On the other hand, hymns that are rich in Biblical content attract heightened scrutiny because they have something to say. Because such hymns commonly are written by denominational authors, they sometimes contain a questionable word or line. Then, brethren who have swallowed the camel of the hymn that says nothing strain at the gnat of ambiguous content. If only the concern aimed at the latter were directed at the former!

For instance, several months ago, I had a conversation with a brother about the hymn “In Christ Alone”, which I believe to be the strongest hymn yet written in this century. However, he was concerned that it taught the false doctrine of penal substitution in the line, “But on that cross as Jesus died/The wrath of God was satisfied.”

For those who aren’t up on their Calvinism, penal substitution is the idea that Jesus did not merely die on the cross in our place. Instead, He was punished on the cross in our place. In bearing our sins, He Himself became morally guilty, so that the wrath of God justly fell upon Him. There is much more to penal substitution than that, and it ties into a number of other Calvinist doctrines (especially the doctrine of eternal security) in complicated and logically intricate ways, but this summary should be enough to make the rest of this post make sense.

Can that couplet in “In Christ Alone” be read as teaching penal substitution? Undoubtedly. In fact, I would go further than that. The authors of “In Christ Alone”, Stuart Townend and Keith Getty, are Scripturally knowledgeable Calvinists. I believe they intended for the couplet to teach penal substitution.

That’s not really the question, though. In the churches of Christ, we have a looong history of reinterpreting Calvinist hymns to suit our doctrinal convictions. The last verse of “The Solid Rock”, anyone?

I think it’s perfectly legitimate for us to do that. The key is that many Calvinist hymns are Scripturally rich, so whatever understanding we apply to the underlying passages, we also can apply to the hymns that quote them. If we are paying attention at all to the words of “The Solid Rock”, we are doing this when we sing it, and there’s no reason why we can’t do the same to “In Christ Alone”.

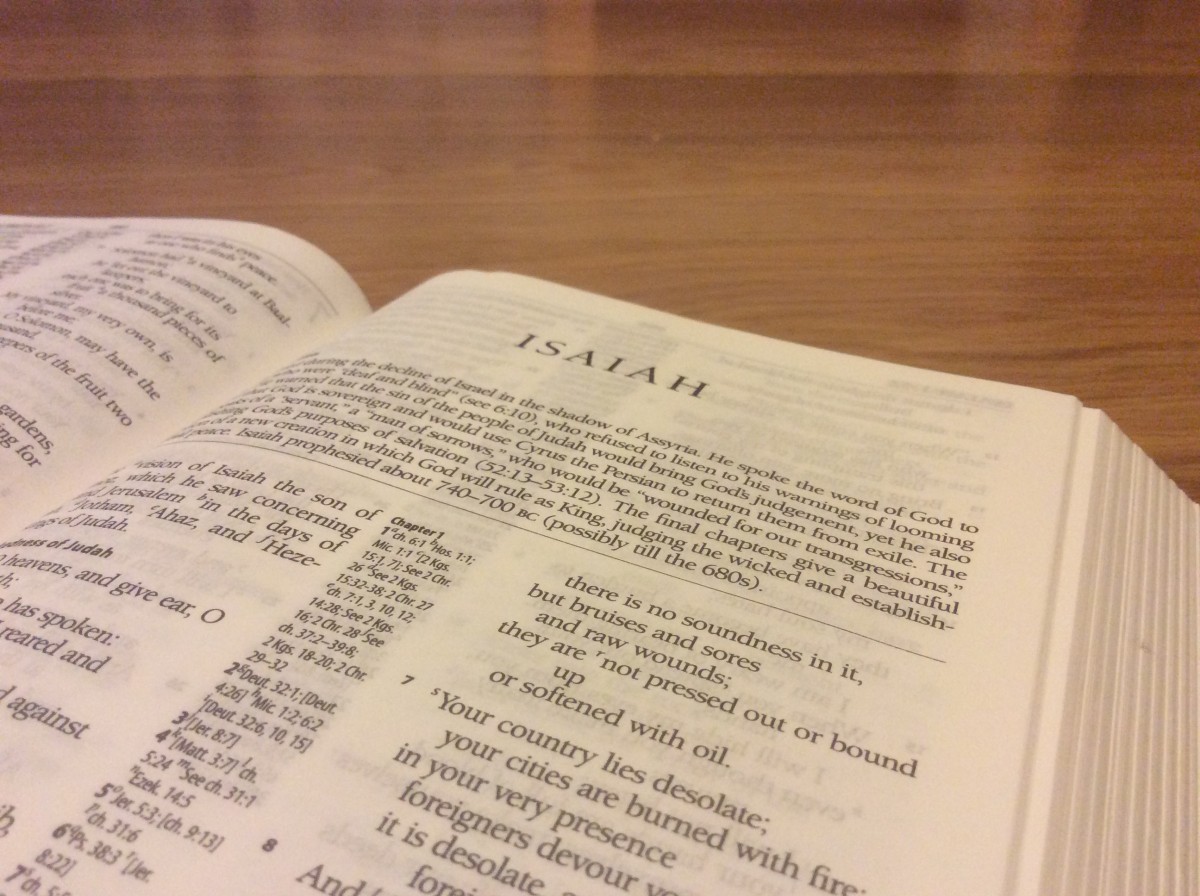

I don’t know what connections others make when they sing that section of “In Christ Alone”, but I can’t help but think of the discussion in Romans of the wrath of God. Romans 1 reports that the wrath of God is revealed against all the unrighteous, but Romans 5 tells us that we can be saved from that wrath through Christ. Why? As Isaiah 53:9-10 reports, even though Jesus had done nothing wrong, God was pleased to crush Him and put Him to death as a guilt offering. If the wrath of God was not satisfied at that point, when was it satisfied? Indeed, I am reasonably certain that Townend and Getty relied on the NASB rendering of Isaiah 53:11 in writing the couplet.

I have no doubt that some will find this explanation, ahem, unsatisfying. Similar quibbles attach to “How Deep the Father’s Love”. In both cases, brethren allow ambiguous language to keep them from singing a doctrinally rich, profoundly meaningful hymn. I think that’s a shame, particularly when the alternative is too often semiliterate nonsense penned by a praise-band leader who might use his Bible for a pillow but not otherwise.

Yes, false doctrine can be drawn from hymns. False doctrine can be drawn from the Bible too. In neither case should the cure for falsehood be the avoidance of truth.

Reflecting on "Hoods in My Hymnal"

Thursday, September 03, 2020

The other day, Steve Wolfgang sent me a link to this article. In it, the author points out that James D. Vaughan, founding father of the Southern gospel genre of hymnody (though not the author of “Love Lifted Me”, despite what the article implies) was a leading figure in the local Ku Klux Klan. James Rowe (who was the author of “Love Lifted Me”) wrote racist lyrics for temperance-movement songs.

This is not terribly surprising. We are talking about Southern gospel, after all, a worship-music movement which flourished in the states of the former Confederacy a hundred years ago. By modern standards, both the ones who wrote those hymns and the ones who originally sang them were dyed-in-the-wool racists. The author implies that we need to “have a conversation” about whether those hymns should remain in the repertoire, the kind of conversation that usually ends with things getting canceled.

Really, though, the issue that the article raises is much larger even than racism. How do we handle hymns that were written by people with significant spiritual problems? From the perspective of New-Testament Christianity, the most famous hymnists of all time come with baggage that is as bad or even worse.

Isaac Watts, author of “When I Survey the Wondrous Cross” and many other great hymns besides, was a hyper-Calvinist minister. Charles Wesley, who wrote “Love Divine”, was the brother and partner of John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist Church. Among modern writers, Keith and Kristyn Getty, the authors of “In Christ Alone”, are staunch and vocal Calvinists. I could say much the same about the authors of literally hundreds of the hymns in our repertoire.

Scripturally speaking, is the false teacher to be preferred to the racist?

One response is to say, “We should not sing such things.” Unless we approve of your life, we aren’t going to sing your hymn. However, if we follow through on such a conviction, our repertoire shrinks by at least 95 percent. Everything from “Abide with Me” to “As the Deer”—gone. Off to the bonfire it all goes!

I think most brethren would consider such a solution a trifle. . . extreme. The alternative, which is what all of us do in practice, is to separate the hymn from the hymnist. I don’t have to agree with everything Isaac Watts stood for to sing “When I Survey.” I only have to agree with “When I Survey”. Nor, indeed, am I endorsing anything about Isaac Watts other than the words that I am singing.

So too, I think, with Southern-gospel hymns written by authors with murky pasts. Yes, they believed, and in some cases wrote, some awful things. However, if our minds are on the human author when we sing a hymn, our minds are in the wrong place.

Those hymns are not memorials to Confederate generals or leaders of the KKK. They are memorials to God. If we use them for their intended purpose, we are glorifying Him. To that, what Scriptural objection can be raised?

The 50 Greatest Hymns of All Time, Revised

Monday, May 04, 2020

Based on input from various readers, I’ve removed four hymns and added four others. The changes are below. Also, it’s likely that I will offer a “lessons learned” post later in the week.

Abide with Me (1847)

All Hail the Power of Jesus’ Name (1779)

All People That on Earth Do Dwell (1560)

IN: Amazing Grace (1779)

Be Still, My Soul (1752)

Be with Me, Lord (1935)

OUT: Footprints of Jesus (1871)

For the Beauty of the Earth (1864)

Give Me the Bible (1883)

Great Is Thy Faithfulness (1923)

Hallelujah! Praise Jehovah! (1893?)

Hallelujah! What a Savior (1875)

He Hideth My Soul (1890)

Higher Ground (1892)

OUT: How Deep the Father’s Love (1995)

How Firm a Foundation (1787)

I Am Thine, O Lord (1875)

I Need Thee Every Hour (1872)

In Christ Alone (2001)

In the Hour of Trial (1834)

It Is Well with My Soul (1873)

Jesus, Draw Me Ever Nearer (2001)

IN: Jesus Loves Me! (1860)

Just As I Am (1834)

Lord, We Come Before Thee Now (1745)

My Jesus, I Love Thee (1862)

Nearer, My God, to Thee (1840)

Nearer, Still Nearer (1898)

IN: O Thou Fount of Every Blessing (1758)

O Worship the King (1833)

On Zion’s Glorious Summit (1803)

Only in Thee (1905)

Our God, He Is Alive (1966)

Purer in Heart, O God (1877)

IN: Rock of Ages (1776)

OUT: Something for Thee (1862)

Stand Up, Stand Up for Jesus (1858)

Sun of My Soul (1820)

Sweet By and By (1867)

Sweet Hour of Prayer! (1845)

Take Time to Be Holy (1874)

OUT: Teach Me Thy Way (1919)

The Battle Belongs to the Lord (1985)

The Last Mile of the Way (1908)

The Solid Rock (1836)

There Is a Habitation (1882)

This World Is Not My Home (1919)

Though Your Sins Be as Scarlet (1887)

‘Tis Midnight, and on Olive’s Brow (1822)

Trust and Obey (1887)

Victory in Jesus (1939)

We Saw Thee Not (1834)

When I Survey the Wondrous Cross (1707)

Why Did My Savior Come to Earth? (1892)