Blog

“The Problem of Other People's Suffering”

Categories: M. W. Bassford, Meditations

I first encountered the classical statement of the problem of human suffering in a religious-studies class in college. The professor wrote on the board, “If God could stop suffering and chooses not to, He is not perfectly good. If God wants to stop suffering and can’t, He is not perfectly powerful. If God is both perfectly good and perfectly powerful, why does suffering exist?”

Though skeptics are fond of the problem of suffering, there are several problems with it. To me, one of the most significant is its assumption that our understanding of the good is the same as God’s understanding. A toddler cannot comprehend why their mother does not feed them candy for every meal and let them stick their fingers into electrical sockets. Is it the mother’s conception of the good that is flawed, or the toddler’s?

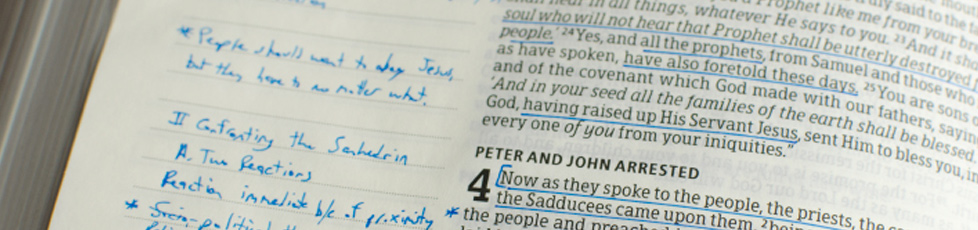

God knows more than we do, has a far better grasp of the consequences of suffering, is far more concerned with the eternal than the earthly, and doesn’t think like us to begin with. The Bible presents Him as a God who is perfectly good, yet whose actions are not subject to human reason. It calls us to trust even when, and especially when, we don’t understand.

All of this, though, is the sort of thing that is discussed in collegiate lecture halls and Wednesday-night Bible classes. It doesn’t have much to do with the actual lived experience of suffering. When you are the one who has lost a child, when you are the one who is grappling with a terminal diagnosis, you are much more concerned with the consequences of God’s existence/nonexistence than you are with proofs to establish either.

If God is and is a rewarder of those who seek Him, suffering and indeed life itself are meaningful. I suffer, yes, but I suffer with hope. My efforts to glorify God are significant and give others the opportunity to make consequential changes in their own life. In the end, I will be blessed with such joy that all my suffering will seem to me as nothing more than momentary, light affliction.

If there is no God, then none of the above applies. Neither my suffering nor my life have meaning. It is impossible for them to be meaningful. I am nothing more than the victim of malignant chance, as everyone will be sooner or later. My efforts to lift others up are pointless. In the end, I will die and be forgotten, with no more significance than the pattern left on the sand by the last wave to wash up on the beach.

If that’s all there is to life, why live? Why go on? Why bother wrestling with the monstrous? The counsel of atheism to the sufferer is the counsel of despair, and it never can be anything else.

Yes, this is an emotional argument, but our reactions to the “rational” arguments about the existence of God are emotionally driven too. Anybody who thinks they can dispassionately reason to fundamental truths about the nature of existence without being powerfully influenced by their desires and fears is a fool. We make such decisions with the Biblical heart, the Eastern mind-and-heart, not the Western mind.

Indeed, the belief that we can rely on the latter is one of the great illusions of Western civilization. The product of such self-deceptive “reasoning” might stand up in the classroom, but suffering forces us to confront the truth. Either we choose to trust in the God whose ways are not our ways, or we reject Him. The former choice is not pleasant, but the latter is unbearable.