Blog

“In Praise of Hymns with Verses”

Categories: Hymn Theory, M. W. Bassford

For the past 40 years or so, the landscape of American sacred music has been dominated by the so-called “worship wars”. These (thankfully bloodless) conflicts have arisen between proponents of rhymed, metered traditional hymns and supporters of freer-form contemporary praise songs. No doctrinal issues are directly at stake here; instead, this is a question of expedience. Which form is most useful for edifying the congregation?

The a-cappella practice of the churches of Christ adds another dimension to the discussion. Most denominational churches have a performer-audience model of worship, and this model doesn’t change whether the performer is using an organ or a guitar.

Within the Lord’s church, though, we use a leader-participant model. We rely on the singing of ordinary Christians, and this reliance means that the opportunities and challenges before us differ from those before denominational worship ministers. The solutions that work for them won’t necessarily work for us, and aspects of worship music that don’t matter to them may well be vital for us.

In turn, this means that we should hesitate to abandon the form of the traditional hymn. The rhymed, metered verse was not invented by Isaac Watts; rather, it is an adaptation of rhymed, metered folk song. All across Western folk music, from sea chanteys to French ballads to medieval Christmas carols, ordinary people have been singing in rhyme and meter for centuries, not because anybody made them, but because it is the form that has evolved to best facilitate the singing of ordinary people. If we also are trying to get ordinary people to sing, we ought to pay attention.

Upon examination, several traits of rhymed, metered, versed hymns commend themselves to our attention. First, they are economical in their use of music. Consider the hymn “O Thou Fount of Every Blessing”. Everyone (including us) sings it to the hymn tune NETTLETON.

NETTLETON is written in rounded-bar form, which many hymn tunes use. A rounded-bar tune consists of four phrases of music with an AABA pattern. Thus, the first, second, and fourth phrases are identical. It’s musically repetitive.

Further repetition arises through the use of multiple verses, as different lyrics are sung to the same music. Thus, by the time a congregation has sung three verses of “O Thou Fount”, it has sung the B phrase three times and the A phrase a whopping nine times.

Musicians often don’t like rounded-bar tunes. They’re bored by them. You sing the same thing over and over and over again. Yawn.

However, what seems like a stumbling block to the musician is a blessing to the congregation. Every church contains a contingent of people who complain about singing “too many new hymns” and an even larger contingent of those who feel the same way but choose to suffer in silence.

Really, though, such brethren don’t object to the new song. They object to the new tune, and they are objecting because they are not particularly musically skilled, can’t read music, and only sing in public when God commands them to. The first time a hymn is sung, they are at a loss, and they can only learn the tune slowly and painfully, by rote. Most people in most congregations fall into this category.

For decades, I’ve heard grumblings from skilled singers that these Christians need to get with the program and learn to read music. I think that solution runs in the wrong direction. Rather, we need to take account of our brethren and introduce new songs that meet them where they are. Because traditional hymns incorporate such a large amount of musical repetition, they do this well. They offer non-musicians the opportunity to sing a great deal of new content while not demanding much from them musically.

The flip side of the coin here is that while versed hymns are repetitive musically, they have the potential to be lyrically rich. The typical praise song is lyrically repetitive. Some hymns are too (and repetition to a certain extent is spiritually useful), but others work their way logically through a subject, like an essay in verse.

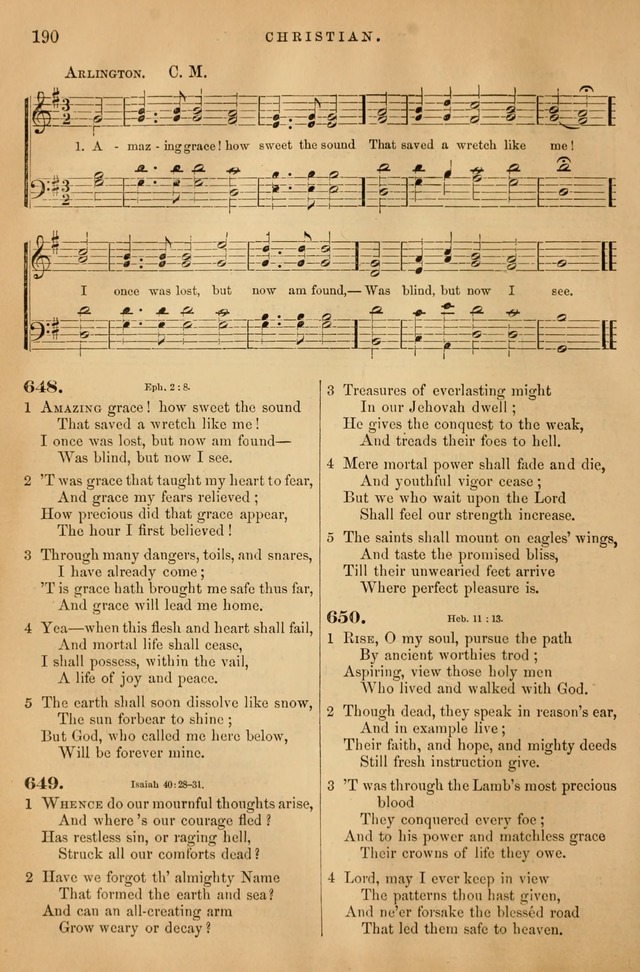

Take, for instance, “Amazing Grace”. The logical structure of the hymn is so strong that we could outline the five verses that usually appear in our hymnals as follows:

- God’s grace is amazing!

- I thought it was amazing when I first believed.

- It has brought me this far in life, and it will continue to protect me.

- It will keep me safe till the end of my life.

- I will celebrate God’s grace forever in heaven.

Hymns with such thoughtful, structured content are important for two reasons. First, they teach a great deal, which amply fulfills the divine commandment to teach and admonish in song. Second, they accustom us to following complex arguments.

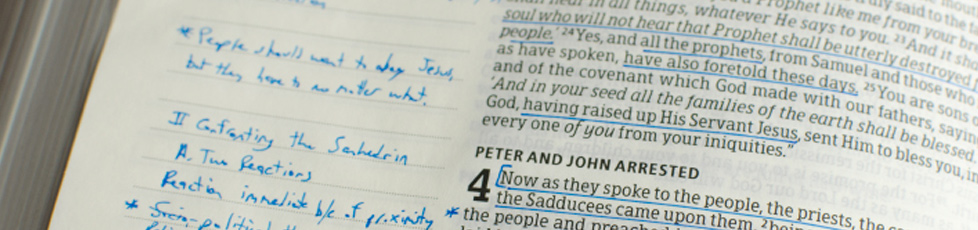

It’s fashionable these days to complain about proof-texting by brethren during Bible study. Certainly, proof-texting has its uses (otherwise inspired authors would not have proof-texted), but the Bible is more than a series of proof texts. When we learn to comprehend entire arguments in the Scripture rather than focusing on isolated verses, we grow greatly in our understanding.

When we sing and pay attention to the words of a structured, content-rich hymn, we necessarily also improve our capacity for understanding the word of God. Conversely, when we sing only repetitive praise hymns that contain no more than a single verse’s worth of content, our ability to appreciate the Bible remains stunted. Our thoughtfulness in worship and our thoughtfulness in study cannot be separated.

The worship wars are not going to be settled anytime soon, and a complete victory for either side isn’t even desirable. There’s a place for contemporary praise songs in our worship services. So too, though, there ought to be a place for traditional hymns. Indeed, the more we return to these ancient forms, the more we will benefit from the wisdom behind them.

This article originally appeared in the February issue of Pressing On.