Blog

“The Online Face of the Kingdom”

Categories: M. W. Bassford, Meditations

Marshal McLuhan, one of the greatest communications theorists of all time, is famous for saying, “The medium is the message.” In other words, the way in which you present information is fully as important as the information itself.

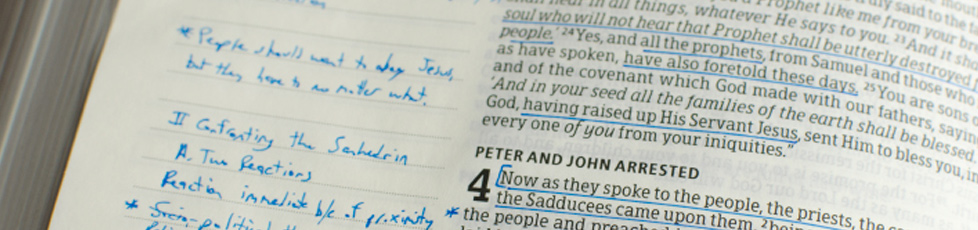

This would not have been news to our brethren in the early church, who adopted the new-to-them format of the codex for the gospels and epistles of the New Testament. Codices were different than scrolls (and both, of course, were equally different from oral tradition). Compare, for instance, the ease of flipping back and forth in a codex with the laborious unrolling and rerolling of a scroll. You’re a lot more likely to use a codex as a reference work, and Bible-as-reference work versus Bible-as-narrative was a truly titanic paradigm shift!

We live in a time that has focused attention on the medium as never before. During the late pandemic, many churches engaged with the Internet in a way that they never had before. If in lockdown, either you were livestreaming services somehow, or you weren’t feeding your people at all!

However, now that life has more or less gone back to normal, the impact of the livestream seems to have faded somewhat. There are still a dozen or so people who tune in regularly to the Jackson Heights livestream: shut-ins (who I’m sure are thrilled that they now have a robust connection to assemblies), the sick, people who are traveling but want to worship with the home folks, and so on. Most of us, though, have reset our assembly and worship experiences to 2019.

I tend to believe the livestream has had only a transitory impact because we weren’t asking what new and different thing we could do. We wanted to do the same old thing: church, except virtual and not quite as good. As we might expect, the medium of “in person” is ideal for many spiritual pursuits. The question that we ought to be asking, though, is whether there are things we can do better online, especially with online video.

I don’t claim to have the answers here, but I did have a fascinating recent experience that led me to conclude that some interesting answers exist. Throughout my adult life, I’ve been involved with a weeklong hymn-writing seminar called the Hymninar. My first year was 1997, and in the time since, I’ve gradually taken on a teaching and mentoring role in it.

This is something with which I am well familiar. I was teaching hymn theory and analyzing students’ hymns before I started preaching the gospel. However, like all other familiar things, the Hymninar got COVID-canceled in 2020, and in 2021, Sumphonia decided to hold the Hymninar virtually over Zoom.

In practice, though, Zoom Hymninar proved to be about as much like in-person Hymninar as a Bible codex was like a Bible scroll. More people participated, in many cases because time, health, or financial constraints would have prevented them from attending in person. Singing was inevitably nonexistent. Teaching was harder. I don’t know why, but it’s a lot harder to pull interaction out of faces on a screen than from people in a classroom.

The most significant differences, though, appeared in collaboration and critique. In an in-person Hymninar, after the class spends a couple of days going through a manual on how to write good hymns, each attendee is asked to write a quality original verse. They write where they please, either in the main classroom or smaller rooms elsewhere. Teachers circulate and offer suggestions. When a verse is far enough along, it gets projected on a screen in the main classroom, and the assembled class provides more critique. Hopefully, by the end of the week, the verse of each student attains the requisite level of quality.

As much as we could, we tried to imitate that format online, with a main Zoom room and breakout rooms where mentors waited for those who wanted help. However, the online version didn’t function like the real-life version. Rather than passively waiting for doom to descend, online attendees actively sought help. The main Zoom room, rather than being sepulchrally quiet like the brick-and-mortar main room, became a place where students engaged in reciprocal editing without prompting from instructors.

Normally, we expect the last day of the Hymninar to be a race against time, with a last few students struggling to finish verses. Some never get there. Not this year. All the writers were solidly done by early afternoon. They did so well, in fact, that they left us scrambling for things to fill the final few hours of the seminar!

Clearly, then, Zoom is a better venue for collaborative hymn editing and critique than a traditional classroom is. Of course, this breaks down spectacularly when it comes to testing hymn tunes, which must be sung, but for text editing, Zoom is superior to real life. Though I can’t say for sure, I suspect that the layer of unreality imposed by Zoom engages people but makes them less inhibited in sharing and receiving criticism.

I know that the intricacies of hymn production aren’t of interest to most Christians. However, this parable has a point. Rather than only asking how the Internet can solve our churches’ huge, pressing problems (like COVID), we should ask how it might solve our low-grade, frustrating problems too. Are there things we want to do that don’t seem to work very well in real life? Maybe they’ll work better in a virtual venue!

To put things another way, we spent 2020 using online media to do almost as good a job because we had to. In the years that follow, we should ask what we want to do with the electronic tools we have because of the very real possibility that they might be better than what we’re doing now. If the medium is the message, it’s time we started investing thought in the medium.

This article originally appeared in _Pressing On_.