Blog

“Why "Break My Heart" Works”

Categories: Hymn Theory

At the end of this year’s new-hymn class at Jackson Heights, we went through and recorded a dozen of the songs we’d learned through the quarter. I’ve spent the past couple of days listening to the CD in the car, not only from a worshiper’s perspective, but from a hymnist’s perspective.

Over the past decade, I’ve slowly learned that there are some things you can’t tell about a hymn or spiritual song until you sing it. For one, there are some arrangements that look fine on the page but prove to be a booger to sing. Most importantly, though, you can’t tell whether a hymn will generate buy-in from brethren until you hear them sing it. There is a difference in sound between singers going through the motions and singers pouring out their hearts in worship.

Buy-in is the single most important attribute of a spiritual song. It determines whether it will be used congregationally or not. If a hymn does not have buy-in, it’s like faith without works. It doesn’t matter how skillfully written or intellectually profound the hymn is. If people don’t want to sing it, it’s dead.

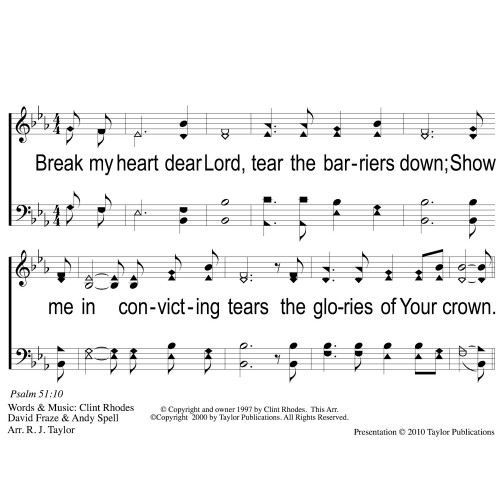

As I was listening to the CD, then, I was listening for the telltale evidence of buy-in. I heard it, among several other places, in the Clint Rhodes song “Break My Heart”. “Break My Heart” is written in a style I don’t use. If I had been invited to edit it, I would have had some technical critiques to offer.

However, if a sacred song draws Christians into worship, it’s doing its job, and “Break My Heart” manifestly does that. I think it works, and I think it works for two reasons:

Accessible Content. “Break My Heart” is a song about the Christian’s struggle with sin. Particularly, it’s about the times when we don’t want to do good, but we want to want to. It’s a plea to God to overcome the stubborn resistance within us so that we can devote ourselves to Him.

Every Christian with an ounce of self-awareness will identify with this struggle. All of us will wrestle with sin for as long as we live, and that conflict exists because our flesh wants to sin. We need God’s help, we know we need God’s help, and so we want to sing a song that is about asking God for help.

Use of Counter-Melody. Recently, I’ve been reflecting a lot on the difference between songs written for a praise band and songs written for the congregation. There are a lot of things that praise bands can do that congregations can’t. Most notably, they can have a more extreme vocal range and use more complicated rhythms. G5 in the melody will murder congregations on Sunday mornings. So too will those dotted-eighth/sixteenth rhythms that mimic the vocal stylings of a lead singer.

However, there are things that congregations do well that praise bands really don’t. First on my list is the employment of counter-melody. Typically, the lead singer of a praise band is The Lead. They don’t want to step back and let somebody else in the band take over for a little bit.

However, congregations enjoy passing the melody back and forth or singing two melodies simultaneously with different rhythms. Many of the most prominent songs that come from a-cappella traditions reflect this. Think “Our God, He Is Alive”, for instance. The same is true of “Break My Heart”. The song really comes alive once you get to the chorus and the alto/tenor counter-melody. They make it musically satisfying.

Fundamentally, I’m a pragmatist. What ought to be is all well and good, but you have to pay attention to what works. “Break My Heart” works, at least in a group that can pull off a tenor counter-melody. Both song leaders and writers ought to pay attention.